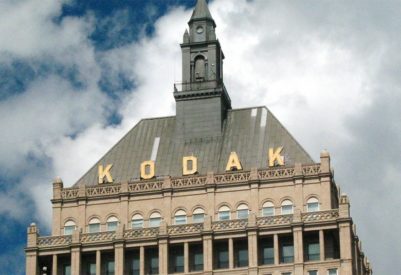

After the 1964 Rebellion, officials at city hall made a commitment to hire more minorities. But executives of big industries like Kodak were not on board. The companies were vowed to not hire or train black workers with blue collar skills for positions other than as custodians.

It was rumored that Kodak funded a private investigation to obtain a list that contained the names of people arrested in the rebellion. The majority was from Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and parts of Alabama. And supposedly the investigation had also revealed that representatives of the United States Government elected in southern states were not lobbying for large manufacturing industries like Kodak and Xerox to build factories in their states.

After the rebellion, manufacturing industries in Rochester for the first time began lobbying southern politicians to build factories in their states, as an option to stop the migration from the south. The investigative report concluded with information that alluded to a fixed position that the efforts of the companies to build factories in southern states failed. The tangible evidence to that conclusion is the continuous protests in the streets leading to Kodak’s administrative offices with people holding signs saying, ‘Kodak Snaps the Shutter on Negroes.’

A strategy to unite the dissidents into a political force was formulated by Minister Franklin Florence, former Pastor of Reynolds Street Church of Christ. Florence decided to invite Saul Alinsky, a political activist from Chicago, Illinois to help organize the movement.

Freddie advised Minster Florence in closed meetings. Florence relied on Freddie’s knowledge and experience as a social activist.

“Freddie believed very strongly that we couldn’t do anything unless we come together,” Constance Mitchell said. “The community was too fragmented at the time, which it still is.”

Inspired by the biblical phrase, ‘Fight the good fight of faith, lay hold on eternal light,’ the anti-segregation voice of the black community in Rochester was organized under the name FIGHT (Freedom, Integration, God, Honor, Today) in June 1965.

Several white churches in Rochester united to support the demands of FIGHT, by forming an organization called Friends of FIGHT.

After a 2-year struggle with the FIGHT organization, Kodak agreed to create a program that will train and employ more than 700 minorities, over an 8-month span. As a social-political organization the opportunities to employ minorities were limited. Therefore, the FIGHT organization had to morphed into a small manufacturing firm in 1967 and reemerged as FIGHTON (now Eltrex Industries) to meet requirements.

The new company demanded equitable consideration and awarding of contracts from the city of Rochester and firms, including Kodak, Xerox and Bausch & Lomb. Florence lost the presidency of FIGHT in 1969 to Freddie’s mentee, Bernard Gifford. Gifford, a postgraduate student at the University of Rochester was studying for a doctorate in Radiation Biology and Biophysics at the U of R.

“In the 1960s we were just starting to understand the genetic code of humans,” Gifford said. “It was the early period of the bio-genetic revolution. Blacks in the research department were rare. I think Freddie was the only one. Freddie didn’t apologize for being black. And during the late 1960s into the 1970s it was important to have a senior black man as a role model.”

Excerpt from: Silent Leader: The Biography of Dr. Freddie L. Thomas available on Amazon and at www.drfreddiethomas.com