(Excerpts from the Film)

Vernon Jarrett: We didn't exist in the other papers. We were neither born, we didn't get married, we didn't die, we didn't fight in any wars, we never participated in anything of a scientific achievement. We were truly invisible unless we committed a crime. And in the BLACK PRESS, the negro press, we did get married. They showed us our babies when born. They showed us graduating. They showed our PhDs.

Phyllis Garland: The black press was never intended to be objective because it didn't see the white press being objective. It often took a position. It had an attitude. This was a press of advocacy. There was news, but the news had an admitted and a deliberate slant.

For over 150 years, African American newspapers were among the strongest institutions in Black America. They helped to create and stabilize communities. They spoke forcefully to the political and economic interests of their readers while employing thousands. Black newspapers provided a forum for debate among African Americans and gave voice to a people who were voiceless. With a pen as their weapon, they were Soldiers Without Swords.

New York, 1826.

In the early 19th century, African Americans were routinely vilified on the pages of the mainstream press and had no way to respond. And by the winter of 1827 an outraged community had had enough. Three blacks gathered on Varick Street in Lower Manhattan and decided that they, too, would use the press as a weapon. They pooled their money and started the first newspaper in the United States to be published by African Americans, Freedom's Journal.

Jane Rhodes: Their whole idea behind Freedom's Journal was to have a voice, an independent voice, an autonomous voice for African Americans. The opening editorial on the front page of Freedom's Journal says, "We mean to plead our own cause."

Vernon Jarrett: "No longer shall others speak for us." What they were saying is that "We don't mind having white Abolitionists plead on our behalf, but we can do it better." And they saw the media as one of the only outlets available for them. Public expression was one of the few weapons that blacks had.

Chosen as the editors of Freedom's Journal were 28-year-old John Russwurm, one of the first black graduates of an American university, and 32-year-old preacher Samuel Cornish. In their inaugural issue, Russwurm and Cornish set out a clear vision for the first black newspaper.

QUOTE FROM FREEDOM'S JOURNAL: "Useful knowledge of every kind and everything that relates to Africa shall find a ready admission into our columns, proving that the natives are neither so ignorant or stupid as they have generally been supposed to be. Whatever concerns us as a people will ever a ready admission in terms of the Freedom's Journal interwoven with all the principal news of the day." Freedom's Journal, March 16th, 1827.

The most influential of the pre-war papers appeared in 1847 with abolitionist leader Frederick Douglas as its editor. In the first issue of The North Star, Douglas also emphasized the need for an independent black press.

QUOTE FROM FREDERICK DOUGLAS: "In the grand struggle for liberty and equality now waging, it is, right, and essential that there should arrive in our ranks authors and editors as well as orators, for it is in these capacities that the most permanent good can be rendered to our cause." Frederick Douglas, December 3rd, 1847.

Jane Rhodes: Presidents read Frederick Douglas' newspapers, although they might not admit it. Senators and -- and congressmen read Frederick Douglas' newspapers. So, Frederick Douglas made it very clear that if you're going to have a movement, if you're going to have a public voice, and if you're going to advocate for social change, the press is -- vital to that effort.

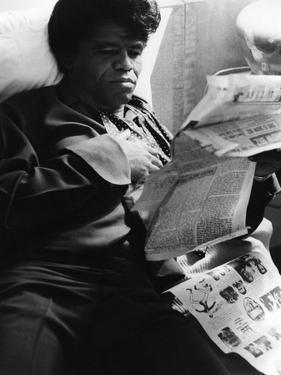

As slaves, African Americans were forbidden to read, but after the Civil War, reading became one of the sweetest fruits of freedom. For many, black newspapers were an introduction the power and the magic of the written word.

Phyllis Garland: After the Civil War there was an enormous burst of energy, a desire to communicate, a desire to connect with black people establishing newspapers in I mean any town, even tiny ones. It was the first opportunity to use the written word without fear of reprisal.

Christopher Reed: I would rank the 19th century African American press as one of the major forces in producing one of the major miracles of that century, pulling African Americans together after slavery into cohesive communities. Whether you're talking about Kansas or Mississippi, New York, it doesn't make any difference -- Washington, these newspapers informed people, elevated morale, built a sense of racial consciousness. You can't overstate the importance of newspapers.

Between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the century, over 500 black newspapers began publication. Many of the papers borrowed printing presses from African American churches and soon the same machines that produced programs for Sunday services were printing the news. Many lasted only a short time, but the papers appeared across the country in cities like Omaha, Mobile, Indianapolis, Cleveland, San Francisco, and in smaller towns like Galveston, Texas, Coffeeville, Kansas, and Langston City, Oklahoma Territory. But in the South, the optimism of the Reconstruction era ended in 1876 when President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew federal protection for the freed slaves.

Jane Rhodes: Once Reconstruction ended, the newspapers were able to maintain a foothold. They did, however, have to be cautious. They had to step lightly in many of those communities where Jim Crow, really controlled the climate of the South.

The White South called it "redemption", but for African Americans the post-Reconstruction period was a reign of terror. Mob violence directed at black Americans was ignored by the federal government and condoned by Southern white newspapers.

QUOTE FROM MEMPHIS COMMERCIAL: "There is nothing' which so fills the soul with horror, loathing and fury as the outraging' of a white woman by a negro. It is the race question in the ugliest, vilest, most dangerous aspect. The negro as a political factor can be controlled, but neither laws nor lynching can subdue his lusts." Memphis Commercial, May 17, 1892.

The 29-year-old editor of another Memphis newspaper, the Free Speech, traveled the South to investigate cases of lynching. The editor was Ida B. Wells. What she found and put into print caused an uproar among White Southerners.

QUOTE FROM IDA B. WELLS: "It is a sacred convention that white women can never feel passion of any sort, high or low, for a black man. Unfortunately, sex don't always square with the convention. And then if the guilty pair are found out, the thing is christened in outrage at once and the woman is practically forced to join in hounding down the partner of her shame."

On June 4th, 1892, while Ida B. Wells was in New York on her first trip North, her paper, the Memphis Free Speech, was attacked by a lynch mob.

Vernon Jarrett: They actually destroyed this woman's press and intended to destroy her body, take her life to the extent that she walked the streets with a pistol under her blouse or apron or, according to legend, two pistols on occasion.

Fearing for her life, Wells did not return South for 30 years. She continued her ground-breaking work on the staff of The New York Age.

Jane Rhodes: She really set the stage for very radical, very activist kind of black journalism. And as a black woman, she was also an inspiration because there were so few African American women who had worked in journalism before. And when they did, it tended to be sort of a social service-oriented journalism, not the sort of powerful, radical, you know, vociferous journalism that said, "We won't stand for this. We must do something about the kinds of violence affecting African Americans."

Vernon Jarrett: I have a teacher who I shall never forget who played a little game with us every Friday afternoon when we were in the first grade before we had learned to read well. She would have all of us kids line up with our chest out and she had given us a name. The little girls, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells. The little boys, Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglas. And one day she told me that I was Robert S. Abbott. And I was supposed to tell my classmates why they should read the Chicago Defender. And I can remember standing up straight, walking up, and I said, "My name is Robert S. Abbott and I am the editor of the Chicago Defender and you ought to read my newspaper because my newspaper's standing up for our race."

Black newspapers sprung up to serve growing communities from New York to the new cities of the west. In 1910 alone, over 275 black newspapers were in print with a combined readership of over half a million. Some, like The California Eagle in Los Angeles, had a new and radical vision of what a paper could be.

Seeking to emulate his hero, Frederick Douglas, John J. Neymour founded The California Eagle in 1879.

The paper was already well established when Charlotta Spears Bass arrived. Her modest appearance concealed boundless energy and uncompromising politics. Bass threw herself fiercely into her work at the Eagle.

Evelyn Cunningham: The black press today seems to react only, react to a -- an issue or a situation or react to something that's in the white press. We very rarely in our black press today initiate, dig up stories or our own. And I think we do need a black press today, very, very much so. We have no voice that tells us about our own lives.

Phyllis Garland: Without this network of communication, it has been far more difficult for African American people to comprehend fully what is happening to them, to be able to have a debate on issues among themselves, and also to develop and to choose their own leaders.

Frank Bolden: I felt bad even when I went to work somewhere else because they taught me how to write, how to make up a newspaper, the value of news, and the value of being truthful. The black press was the advocate of all our dreams, wishes, and desires. I still think it was a greatest advocate for equal and civil rights that black people ever had in America. It had an effect on everybody.