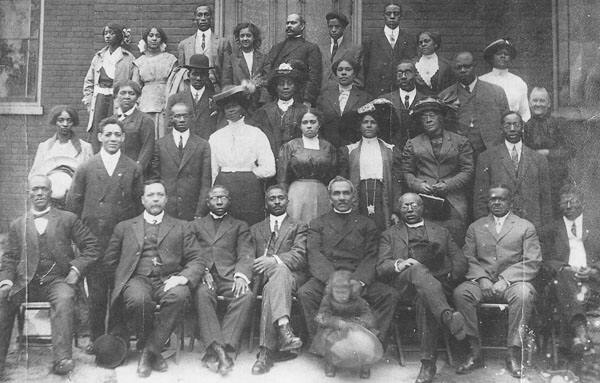

Rochester is well known for its ties to former slave, abolitionist, orator, and publisher Frederick Douglass, who made his home there in 1847. As early as 1810, freed blacks were living in Western New York and soon established Rochester’s first African American neighborhood located on High Street that later became Clarissa Street. The neighborhood was located in the Third Ward.

Twenty years later, Reverend Thomas James, an escaped slave, found the Memorial African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in 1830. The church became an essential hub for the Underground Railroad, Douglass’s abolitionist newspaper (The North Star) and for Susan B. Anthony’s women suffrage movement. A slow progressive flow of stable black families continued to move into the Third Ward with each passing decade.

During the Great Depression general unemployment was 40 percent and among Blacks 70 percent, but they were able to keep their families together. The Third Ward had a sound population composed of upward mobile families like the Dubois, Stevens, Grays, Coles, and Walls.

You had two doctors, Lunsford and Jordan, two dentists-Lindsey and Levy, and two morticians-Latimore and Myers. The Third Ward’s stable population would abruptly change following a massive migration of black people fleeing the South.

Rochester is home to several pioneering companies, including Eastman Kodak, Bausch & Lomb, Xerox and Rochester Products Division, an auxiliary of General Motors. Those fleeing the South considered Rochester an ideal destination because of its history of progressive social justice and reputation for migrant jobs.

The city of Rochester in 1945 had a population of 5,000 black people.

By 1964, almost 32,000 black people lived in Rochester with the greater percentage arriving from the South. A number of settlement houses were organized in Rochester, such as Baden Street in 1901, to ease the transition of people migrating from all parts of Europe.

Several years later, the Genesee Settlement House and Lewis Street Center were established to accommodate the continuous influx of Jewish, Italian, and Russian immigrants.

The goals set by the houses were to “pursue the elimination of the causes of poverty and to reduce the level of negative social problems associated with being disadvantaged.”

During the massive migration of black people from 1945 to 1960, no community instrument existed in Rochester to ease the transition. The only accessible instrument was Baden Street beginning to move into the area of serving African Americans.

The newcomers largely settled in the Third and Seventh Wards. The Seventh Ward with Joseph Avenue at its heart was the only neighborhood with public housing in the 1950s. Most African Americans lived in a 12-block area in the Third Ward and a 12-block area in the Seventh Ward, where many dilapidated housings were concentrated.

Third Ward resident Constance Mitchell said, “Rochester had a very low unemployment rate, but jobs were not available. The factories were not open to minorities.

“It was well known, if minorities applied for jobs in the factories their applications would end up in File 13-the wastebasket,” she said. “People coming to Rochester from the southern states weren’t aware of the struggles, so they kept coming. And when Dr. Freddie Thomas started coming around, the black population in Rochester was beginning to realize, if they were to control anything to a certain degree it would be within their own communities.”

Other than turning their focus towards community development to establish social mobility, African Americans in Rochester had few options to improve their livelihoods.

By the mid-1950s, Clarissa Street had become a main commercial district of the Third Ward. Businesses included the Gibson Hotel, Latimer Funeral Home, Ray Daniel Barbershop, Scotty Pool Hall, Smitty Birdland, LaRue and Pendleton Restaurants and the Vallot Tavern, just to name a few. The Third Ward nightclubs such as the Pythodd Club, the Elk Club and Dan Restaurant and Grill, became famous for jazz music. Grocery stores, bakeries, pharmacies, and clothing shops occupied both sides of Jefferson Avenue. And across-town, Joseph Avenue became a main commercial district where minorities were majority stakeholders.

The Black community was transformed into one big family. They were conscious of behaving kindly to each other. They were being Black, buying Black and thinking Black.

A unity compelled by segregation.

The atmosphere in Rochester coincided with books written during the Harlem Renaissance that Freddie read as a kid. The presence of racial pride and bustling minority-owned businesses was reminiscent of the period.

Freddie described his arrival in the city in 1952 as, “Finding Heaven.” “I came to Rochester to visit a fraternity brother of mine,” Freddie recalls. “It was so peaceful here, I stayed for three days.... then a week.... then two weeks.... then I jumped in my car to get my belongings from New York City and move myself here.”

Excerpt from: Silent Leader: The Biography of Dr. Freddie L. Thomas

Available at: www.drfreddiethomas.com and Amazon and www.drfreddiethomas.com