Southwest Tribune Newspaper

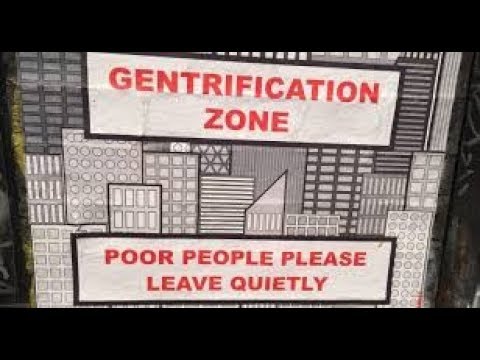

Gentrification describes a process where wealthy, college-educated individuals begin to move into poor or working-class communities, often originally occupied by communities of color.

The poor communities of color who tend to inhabit neighborhoods targeted for gentrification were often the victims of unfair housing policies.

Most scholars point to two interrelated socio-economic causes of gentrification. The first of these, supply and demand, consists of demographic and economic factors that attract higher-income residents to move into lower-income neighborhoods. The second cause, public policy, describes rules and programs designed by urban policymakers to encourage gentrification as a means of achieving “urban renewal” initiatives.”

“The supply-side theory of gentrification is based on the premise that various factors like crime, poverty, and general lack of upkeep will drive the price of inner-city housing down to the point where affluent outsiders find it advantageous to buy it and renovate it or convert it to higher-value uses, according to Think Co.

An abundance of low-priced homes, coupled with convenient access to jobs and services in the central city, increasingly make inner-city neighborhoods more desirable than the suburbs to people who are more financially able to convert inner-city housing to higher-priced rental property or single-family homes.

Demographics have shown that young, wealthy, childless people are increasingly drawn to gentrifying inner-city neighborhoods. Social scientists have two theories for this cultural shift. In search of more leisure time, young, affluent workers are increasingly located in central cities near their jobs.

The blue-collar manufacturing jobs that left the central cities during the 1960s have been replaced by jobs in financial and high-tech service centers. Since these are typically high-paying white-collar jobs, neighborhoods closer to the inner-city attract affluent people looking for shorter commutes and the lower home prices found in aging neighborhoods.

Secondly, gentrification is driven by a shift in cultural attitudes and preferences. Social scientists suggest that the growing demand for central city housing is partially the result of a rise in anti-suburban attitudes. Many wealthy people now prefer the intrinsic “charm” and “character” of older homes and enjoy spending their leisure time—and money—restoring them.

As older homes are restored, the overall character of the neighborhood improves, and more retail businesses open to serve the growing number of new residents.

Demographics and the housing market factors alone are rarely enough to trigger and maintain widespread gentrification. Local government policies that offer incentives to affluent people to buy and improve older homes in lower-income neighborhoods are equally important. For example, policies that offer tax breaks for historic preservation, or environmental improvements encourage gentrification.

Similarly, federal programs intended to reduce mortgage loan rates in traditionally “under-served areas” make buying homes in gentrifying neighborhoods more attractive.

Finally, federal public housing rehabilitation programs that encourage the replacement of public housing projects with less dense, more income-diverse single-family housing have encouraged gentrification in the neighborhoods once blighted by deteriorating public housing.

While many aspects of gentrification are positive, the process has caused racial and economic conflict in many American cities.

The results of gentrification often disproportionately benefit the incoming homebuyers, leaving the original residents economically and culturally deprecated.

Originating in London during the early 1960s, the term gentrification was used to describe the influx of a new “gentry” of wealthy people into low-income neighborhoods. In 2001, for example, a Brookings Institute report defined gentrification as “…the process by which higher-income households displace low-income residents of a neighborhood, changing the essential character of that neighborhood.”

Even more recently, the term is applied negatively to describe examples of “urban renewal” in which wealthy—usually white—new residents are rewarded for “improving” an old deteriorating neighborhood at the expense of lower-income residents—typically people of color—who are driven out by soaring rents and the changing economic and social characteristics of the neighborhood.

Two forms of residential racial displacement are observed most often. Direct displacement happens when the effect of gentrification leaves current residents unable to pay increasing housing costs or when residents are driven out by government actions like forced sale by eminent domain to make way for new, higher-value development.

Some existing housing may also become uninhabitable as the owners stop maintaining it while waiting for the best time to sell it for redevelopment.

Indirect residential racial displacement occurs when other low-income individuals cannot afford older housing units being vacated by low-income residents. Indirect displacement can also occur due to government actions, such as discriminatory “exclusionary” zoning laws that ban low-income residential development.

Residential racial displacement resulting from gentrification is often considered a form of de-facto segregation, or the separation of groups of people caused by circumstances rather than by law, such as the Jim Crow laws enacted to maintain racial segregation in the American South during the post-Civil War Reconstruction era.”

The lack of affordable housing, long a problem in the United States, is made even worse by the effects of gentrification. According to a 2018 report from the Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies, nearly one in three American households spend more than 30% of their income on housing, with some ten million households spending more than 50% of their income on housing costs.

As part of the gentrification process, older affordable single-family housing is either improved by the incoming residents or replaced by high rent apartment projects. Other aspects of gentrification, such as government imposed minimum lot and home sizes and zoning laws banning apartments also reduce the pool of available affordable housing.

For urban planners, affordable housing is not only hard to create, but it is also hard to preserve.

Often hoping to encourage gentrification, local governments sometimes allow subsidies and other incentives for affordable housing construction to expire. Once they expire, owners are free to convert their affordable housing units to more expensive market-rate housing.

On a positive note, many cities are now requiring developers to build a specified percentage of affordable housing units along with their market-rate units.

Often a byproduct of racial displacement, cultural displacement occurs gradually as the departure of long-time residents changes the social character of the gentrifying neighborhood.

As old neighborhood landmarks such as historically black churches close, the neighborhood loses its history and its remaining long-time residents lose their sense of belonging and inclusion. As shops and services increasingly cater to the needs and traits of new residents, remaining long-time residents often feel like they have been dislocated despite still living in the neighborhood.

As upper- and lower-income residents replace the original lower-income population, the political power structure of the gentrifying neighborhood can also change. The new local leaders begin to ignore the needs of the remaining long-time residents.

As the long-time residents sense their political influence evaporating, they further withdraw from public participation and become more likely to physically leave the neighborhood.