All our receivership schools will be transitioning to Community School models. While this is good news, it is going to be a long process that we are going to have to watch closely and make sure it does not stall.

The Mayor is a big proponent of Community Schools. John Laing found the pages that pertain to Local Busing and Community Schools in the Mayor's Rochester 2034 comprehensive plan and they are music to our ears. Just about everything we have been pushing for during the past 7 years is in there.

John and I have an appointment to meet with Mayor Warren on June 11 to try to get things moving on local busing and Dan Lowengard is setting up a meeting to introduce us to Terry Dade next week so we can develop a working relationship with the new Superintendent.

John Boutet, co-chair Education Committee, SW Common Council

ROCHESTER 2034 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN INITIATIVE AREA 3-DRAFT

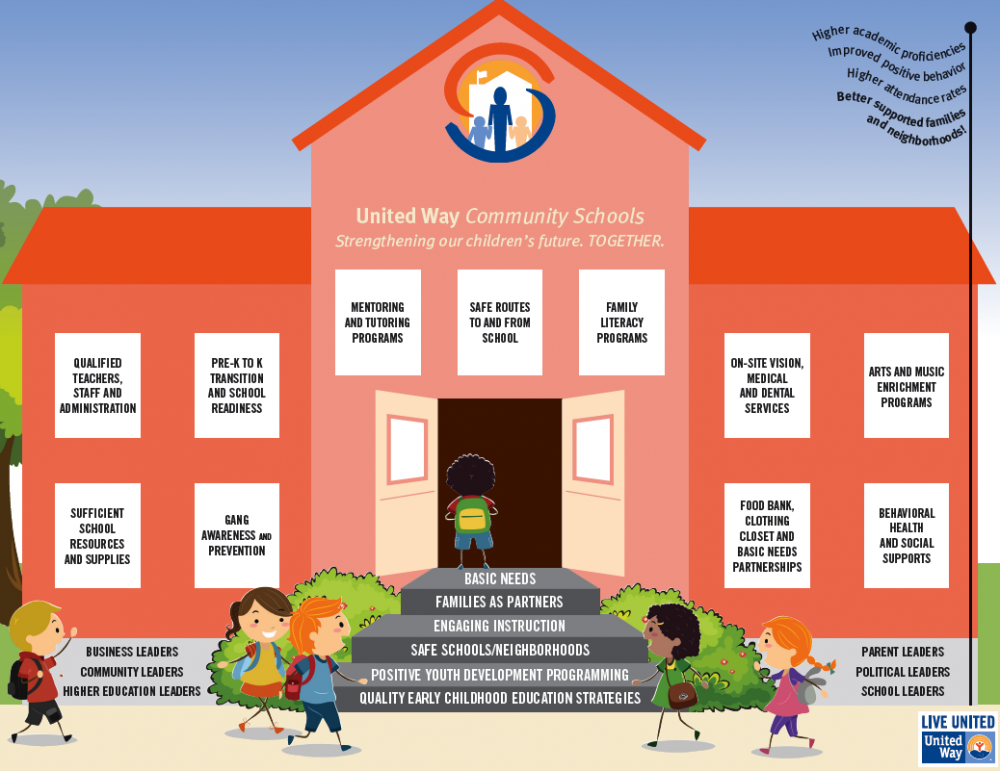

Neighborhood schools are common throughout cities and towns across the country. Students enrolled are primarily or entirely drawn from the surrounding area so as to reduce transportation costs and promote a strong connection between the school and neighborhood. Community schools are a more intensive model; they similarly draw students from nearby areas but also provide a variety of services and activities to all local residents in the form of a “hub of access”.

In the early 2000s, RCSD transitioned to a choice-based model of schooling, called the Managed Choice Policy, moving away from the neighborhood school model that had been in place for generations. One of the objectives of the change, in addition to providing more equitable choices to families regardless of where they live, was to deconcentrate poverty by not limiting schools in the most impoverished areas to drawing students exclusively from the surrounding neighborhood. Conversely, schools in more stable areas would be made accessible to students from outside of the surrounding neighborhood.

After more than 15 years of Managed Choice, the district should reexamine if either of those objectives, or any of the other foundation goals, have been met by the system. The City of Rochester remains similarly racially and economically segregated, both within the district and within the region, as it was when the policy was instituted. Poverty overall has only gotten worse while schools continue to struggle. The condition of the district remains the primary reason for many middle-class families leaving the city or never considering city living.

Currently, more than 80% of children in the RCSD attend elementary schools outside of their neighborhood. This has substantial implications for district and household transportation costs, relationships between schools and their surroundings, and the ability of families to participate in their children’s schools. Parental involvement is well documented as a major contributing factor to a child’s educational attainment. Also, around half of students in the district do not engage in the lottery/choice process at all, foregoing the benefits of school choices and necessitating district staff to make decisions that are absent of any formal guidance.

Another predicament created by the current model relates to busing. Currently, New York State only reimburses school district costs for transporting students more than 1.5 miles. Closer schools require families to identify their own transportation solution. In many cases, families choose schools that are far from their home because it is easier to put children on a bus in the morning than to walk, bike, or drive them to a school that is nearby.

They often make this choice as well because long bus rides present a free, albeit far from ideal, before-school and after-school childcare option for parents in inflexible or insecure employment situations. This dynamic is on top of the $66 million spent every year on busing students in far flung, haphazard patterns across the city. While the State reimburses the School District for 90% of those costs, a $6.6 million local burden is still a substantial cost for a district where the vast majority of students live short distances – often reasonable walking distances – from an elementary school.

The sheer mileage represented by a $66 million transportation budget, regardless of where the money comes from, has significant implications for air quality, energy consumption, and energy resiliency.

The disincentive to choosing neighborhood schools would need to be addressed through creative transportation and wrap-around service solutions. A return to the neighborhood or community school model, even if done incrementally, could have a positive impact on both schools and their surroundings. Throughout the Rochester 2034 process, residents and neighborhood groups spoke of the desire for stronger connections to and partnership opportunities with their nearby school.

Most noted that relationship to be non-existent and many were not aware of any neighborhood families that attended the local elementary school. Having the local school serve as an anchor institution could be particularly beneficial for areas of disinvestment that lack notable community assets.

Exploring neighborhood and community schools Continued P. 222, 223

In addition to the opportunity for stronger involvement from nearby community groups, the neighborhood or community school approach would allow local families to be more engaged with their kids’ school than if the facility was on the other side of town. Even if a neighborhood school was predominately made up of low-income families – a scenario that has not been eliminated by the Managed Choice model – at least those families would have the chance to form stronger bonds with neighborhood parents, students, and school faculty. They would also have far more convenient access to the school for parent-teacher meetings, volunteer opportunities, school assemblies, and other enriching activities. Lastly, having a community school would greatly enhance the identity and sense of pride of the neighborhood, regardless of the school’s performance.

The RCSD is now experimenting with elements of the neighborhood/community school approach for certain buildings. In partnership with the City of Rochester and Ibero-American Action League, Enrico Fermi School No. 17 is envisioned to be a community school, hoping to draw students primarily from the nearby JOSANA neighborhood. The school also offers a full menu of wrap-around services to students and their families, including medical, dental, mental health, and human services. This “hub of access” model positions the school as a holistic resource for an area facing entrenched poverty. Its success is highly reliant on most of the enrolled families to live near the school, a condition they have not yet achieved but hope to in coming years. If successful, the model could be repeated but it requires additional funding.

At John James Audubon School No. 33, a recent change allows for children moving on from the elementary school in the Beechwood neighborhood to automatically enroll in the closest 6-12 campus, East Lower and Upper School. Parents can opt out of this policy if they would like to pursue other options, but they are no longer forced to go through a process where they may not get into East even if it is not their first choice. This creates a more deliberate relationship between the Beechwood neighborhood and its two school facilities. However, School No. 33 is not a neighborhood school to begin with, so the community connection will be limited until that policy is addressed.

The City of Rochester supports and recommends the district’s continued adoption of a neighborhood or community school approach at the elementary school level. These models, or specific elements of the models, may also be effective in certain middle school or high school facilities. However, it may not be practical district wide as there are far fewer schools at those grade levels.

A recent RCSD School Board committee examined these issues in depth and recommended some changes to the system, including:

— guaranteeing every student, a seat in the school closest to their house;

— replacing the three school selection zones with a system allowing children to apply to any of the three closest schools, or to the citywide schools; and

— providing busing for students who live within 1.5 miles of a school.

In December 2018, Mayor Warren conducted a series of input sessions around the challenges and opportunities facing the RCSD. As part of a series of poll questions, 90% of participants indicated they would support more community schools throughout the district.

The City recommends further exploration of these and similar strategies that will balance the complexities of a large district with the benefits of neighborhood and community schools. In particular, the City desires to partner with the RCSD to examine how the benefits of these models go well beyond education. Closing opportunity and achievement gaps and promoting equitable outcomes for all children requires a comprehensive approach that encompasses school policies as well as the investments that the City and community partners put into each neighborhood.